1. SAUDI ARABIA

Saudi Arabia's War on Witchcraft

A special unit of the religious police pursues magical crime aggressively, and the convicted face death sentences.

The sorceress was naked.

The sight of her bare flesh startled the prudish officers of Saudi Arabia's infamous religious police, the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV), which had barged into her room in what was supposed to be a routine raid of a magical hideout in the western desert city of Madinah's Al-Seeh neighborhood. They paused in shock, and to let her dress.

The woman -- still unclothed -- managed to slip out of the window of her apartment and flee. According to the 2006 account of the Saudi Okaz newspaper, which has been described as the Arabic equivalent of the New York Post, she "flew like a bird." A frantic pursuit ensued. The unit found their suspect after she had fallen through the unsturdy roof of an adjacent house and onto the ground next to a bed of dozing children.

They covered her body, arrested her, and claimed to uncover key evidence indicating that witchcraft had indeed been practiced, including incense, talismans, and videos about magic. In the Al Arabiya report, a senior Islamic cleric lamented that the incident had occurred in a city of such sacred history. The prophet Muhammad is buried there, and it is considered the second most holy location in Islam, second to Mecca. The cleric didn't doubt the details of the incident. "Some magicians may ride a broom and fly in the air with the help of the jinn [supernatural beings]," he said.

The fate of this sorceress is not readily apparent, but her plight is common. Judging from the punishments of others accused of practicing witchcraft in Saudi Arabia before and since, the consequences were almost certainly severe.

In 2007, Egyptian pharmacist Mustafa Ibrahim was beheaded in Riyadh after his conviction on charges of "practicing magic and sorcery as well as adultery and desecration of the Holy Quran." The charges of "magic and sorcery" are not euphemisms for some other kind of egregious crime he committed; they alone were enough to qualify him for a death sentence. He first came to the attention of the religious authorities when members of a mosque in the northern town of Arar voiced concerns over the placement of the holy book in the restroom. After being accused of disrupting a man's marriage through spellwork, and the discovery of "books on black magic, a candle with an incantation 'to summon devils,' and 'foul-smelling herbs,'" the case -- and eventually his life -- were swallowed by the black hole of the discretionary Saudi court system.

The campaign of persecution has shown no signs of fizzling. In May, two Asian maids were sentenced to 1,000 lashings and 10 years in prison after their bosses claimed that they had suffered from their magic. Just a few weeks ago, Saudi newspapers began running the image of an Indonesian maid being pursued on accusations that she produced a spell that made her male boss's family subject to fainting and epileptic fits. "I swear that we do not want to hurt her but to stop her evil acts against us and others," the man told the news site Emirates 24/7.

According to Adam Coogle, a Jordan-based Middle East researcher for Human Rights Watch who monitors Saudi Arabia, the relentless witch hunts reveal the hollowness of the country's long-standing promises about liberalizing its justice system.

In a country where public observance of any religion besides Islam is strictly forbidden, foreign domestic workers who bring unfamiliar traditional religious or folk customs from Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Africa, or elsewhere can make especially vulnerable and easy targets. "If they see these [folk practices or items] they immediately assume they're some kind of sorcery or witchcraft," he said.

The Saudi government's obsession with the criminalization of the dark arts reached a new level in 2009, when it created and formalized a special "Anti-Witchcraft Unit" to educate the public about the evils of sorcery, investigate alleged witches, neutralize their cursed paraphernalia, and disarm their spells. Saudi citizens are also urged to use a hotline on the CPVPV website to report any magical misdeeds to local officials, according to the Jerusalem Post.

According to a director of the religious police's witchcraft division in Riyadh, the unit provides confidentiality to informants. "We deal with sorcerers in a special way. No one should think that we mention the name of whomever files a report about sorcery," Sheikh Adel Faqih told the Saudi Gazette. In 2009 alone, at least 118 people were charged with "practicing magic" or "using the book of Allah in a derogatory manner" in the province of Makkah, the country's most populous region.

Faqih also claimed that the process of arresting someone for crimes of magic involved more than just receiving a tip from a neighbor or employer. A formal investigation would be pursued, and "information must be collected before an arrest can be made." What sort of information do they need? The answer was unsurprisingly vague and innocuous: if the suspect sought to purchase "an animal with certain features." For example, "he asks for a sheep to be killed without mentioning Allah's name and asks to stain the body with the animal's blood or if he asks for similar unusual things."

By 2011, the unit had created a total of nine witchcraft-fighting bureaus in cities across the country, according to Arab News, and had "achieved remarkable success" in processing at least 586 cases of magical crime, the majority of which were foreign domestic workers from Africa and Indonesia. Then, last year, the government announced that it was expanding its battle against magic further, scapegoating witches as the source of both religious and social instability in the country. The move would mean new training courses for its agents, a more powerful infrastructural backbone capable of passing intelligence across provinces, and more raids. The force booked 215 sorcerers in 2012.

The most aggressive pursuit of witches tends to be in the interior of the Arabian peninsula, a parcel of the country that hosts the capital city Riyadh and many of the most dedicated followers of Salafism, the ultra-conservative school of Sunni Islam that the government enforces throughout the country in its religious courts.

Wresting the country's criminal proceedings from the grip of one of the strictest strains of Islam would involve more than just the development of a more progressive outlook; it would require cosmic revisions in Saudi history and religious identity.

The Saudi government and many of its citizens subscribe to the 18th-century teachings of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, a revivalist Islamic scholar who called for a return to literal interpretations of the Quran, and for the abandonment of folk rituals that had developed around the worship of Islamic shrines and grave sites. According to historian Vladmir Borisovich Lutsky:

He sharply criticised such superstitious survivals as fetishism and totemism, which, to him, were indistinguishable from idolatry. Formally all the Arabs were Moslems. But, in reality, there existed many local tribal religions in Arabia. Each Arab tribe, each village had its fetish, its beliefs and rites. The variety of religious forms that stemmed from the primitive level of social development and the lack of cohesion between the countries of Arabia were serious obstacles to political unity. Abd el-Wahhab set up against this religious polymorphism a single doctrine called tauhid (unity).......

The Wahhabis fought against the survivals of local tribal cults. They destroyed the tombs of the saints, and forbade magic fortune-telling. But at the same time their teachings were directed against official Islam.

Under Wahhabi doctrine, magic is seen as a serious affront to the pure and exclusive relationship one is supposed to share with Allah.

But belief in the supernatural and magic is actually quite common in Muslim culture. According to the Quran, the jinn are demonic supernatural beings that were created out of fire at the same time as man. Some believe that jinn have the power to cause harm, and it is not uncommon for the possessed to visit faith healers or sorcerers tasked with ridding the evil.

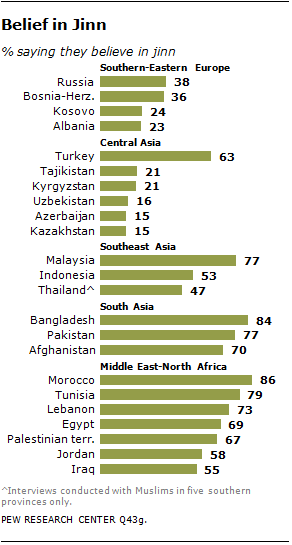

According to the Pew Research Center's Religion and Public Life Project:

In most of the countries surveyed, roughly half or more Muslims affirm that jinn exist and that the evil eye is real. Belief in sorcery is somewhat less common: half or more Muslims in nine of the countries included in the study say they believe in witchcraft.

Accusations of jinn worship and witchcraft once even touched the administration of former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, when his advisers and aides were arrested on charges of black magic. Ahmadinejad denied the charges, but a sorcerer well-known among the ruling class claimed that he met with the President at least twice and gathered intelligence for him on "Jinn who work for Israel's intelligence agency, the Mossad, and for the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency," according to the Wall Street Journal.

According to the Pew survey, the majority of Muslims agree that Islam restricts making contact with jinn or using magic. But Wahhabism is particularly opposed to this notion, according to Muhammad Husayn Ibrahimi's analysis of the sect:

Based on some verses of the Qur'an, Shaykh Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab, Ibn Taymiyyah and the contemporary Wahhabis regard seeking help from other than God or asking for their intercession {shafa'ah} as an act of polytheism. Their main proof is the phrase, "other than God" in verse 18 of Surah Yunus. The Wahhabis regard the prophets, saints, idols, the jinn, and the dead as the most vivid manifestations of this verse.

This might explain why Saudis, many of whom are devout Wahhabi practitioners, are so fierce when it comes to the pursuit of witches.

The courts are controlled by judges -- commonly religious clerics -- who have unlimited latitude to interpret and define the content of witchcraft crime, the details of which are not articulated in a spare, barely existent penal code. They can also mete out capital punishments as they see fit. Saudi Arabia ranks third behind China and Iran for its number of executions. Evidence in these cases is limited to witness testimony and the presentation of the "magical" items discovered in the possession of the accused.

The Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia did not respond to requests for comment on the specifics of its dealings with witchcraft crime.

The ability to defend against the charges seems to depend on the caprice of the particular judge assigned to the case. In the 2006 case of Fawza Falih, who was sentenced to death on charges of "'witchcraft, recourse to jinn, and slaughter' of animals," she was provided no opportunity to question the testimonies of her witnesses, was barred from the room when "evidence" was presented, and her legal representation was not permitted to enter court. After appeals by Human Rights Watch, her execution was delayed, but she died in prison as a result of poor health.

The police can also use questionable tactics. In 2008, a well-known Lebanese television personality, Ali Hussain Sibat, who made a living by telling callers' fortunes and instructing them on other superstitious matters, was lured into an undercover sting operation while making a religious pilgrimage to Mecca. According to the New York Times, he was arrested shortly after the police recorded conversations he held about providing a magical elixir to a woman that would force her husband to separate from his second wife. His death sentence was later stayed after outcry from international human rights organizations.

Belief in magic is so widespread that it is often invoked as a defense in Sharia courts. "If there's an employer dispute -- say the migrant domestic worker claims she wasn't paid her wages or her conditions are unlivable -- a lot of times what happens unfortunately is the defendant makes counterclaims against the domestic worker," Coogle said. "And a lot of times they'll make counterclaims of sorcery, witchcraft, and that sort of thing."

Domestic workers, many of whom who are not fluent in Arabic, face significant challenges in defending themselves against these charges, according to Coogle. Sometimes, he says, "they don't even know what's happening." "I think that there are cases where the authorities will provide translation, but I'm told the translation isn't always available and isn't always reliable." Many don't have the resources to hire a lawyer, so they are often representing themselves, unless a human rights organization takes on their case.

Even then, they must face a religious cleric who serves simultaneously as a judge and a prosecutor and can often introduce new charges or modify existing ones during the course of the proceedings. "When you have a situation that's so arbitrary and left to the discretion of a judge, women without the means to defend themselves can sort of be left alone," he said. Though some of the cases receive international attention, Coogle expects that many don't make headlines at all. "Given the isolation of these individuals," he said, "I just expect that a lot happens that we don't know about."

CREDIT: THE ATLANTIC

2. BBC LONDON

Saudi man executed for 'witchcraft and sorcery'

A Saudi man has been beheaded on charges of sorcery and witchcraft, the state news agency SPA says.

The man, Muree bin Ali bin Issa al-Asiri, was found in possession of books and talismans, SPA said. He had also admitted adultery with two women, it said.

The execution took place in the southern Najran province, SPA reported.

Human rights groups have repeatedly condemned executions for witchcraft in Saudi Arabia.

Last year, there were reports of at least two people being executed for sorcery.

Mr Asiri was beheaded after his sentence was upheld by the country's highest courts, the Saudi news agency website said.

No details were given of what he was found guilty of beyond the charges of witchcraft and sorcery.

Amnesty International says the country does not formally classify sorcery as a capital offence.

But the BBC's Arab Affairs Editor, Sebastian Usher, says there is a very strong prohibition of some practices from the country's powerful conservative religious leaders.

Some, he explains, have repeatedly called for the strongest possible punishments against anyone suspected of sorcery - whether they are fortune tellers or faith healers.

In 2010, a Lebanese television presenter of a popular fortune-telling programme was arrested while on pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia.

Though sentenced to death, after pressure from his government and human rights groups, he was freed by the Saudi Supreme Court, which found that he had not harmed anyone.

More recent cases of death on charges of sorcery include that of a Saudi woman, executed for committing sorcery and witchcraft in December, in the northern province of Jawf, and that of a Sudanese man executed in September, despite calls led by Amnesty International for his release.

3. SAUDI ARABIA

Saudi woman executed for 'witchcraft and sorcery'

A Saudi woman has been executed for practising "witchcraft and sorcery", the country's interior ministry says.

A statement published by the state news agency said Amina bint Abdul Halim bin Salem Nasser was beheaded on Monday in the northern province of Jawf.

The ministry gave no further details of the charges which the woman faced.

The woman was the second person to be executed for witchcraft in Saudi Arabia this year. A Sudanese man was executed in September.

'Threat to Islam'

BBC regionalist analyst Sebastian Usher says the interior ministry stated that the verdict against Ms Nasser was upheld by Saudi Arabia's highest courts, but it did not give specific details of the charges.

The London-based newspaper, al-Hayat, quoted a member of the religious police as saying that she was in her 60s and had tricked people into giving her money, claiming that she could cure their illnesses.

Our correspondent said she was arrested in April 2009.

But the human rights group Amnesty International, which has campaigned for Saudis previously sentenced to death on sorcery charges, said it had never heard of her case until now, he adds.

A Sudanese man was executed in September on similar charges, despite calls led by Amnesty for his release.

In 2007, an Egyptian national was beheaded for allegedly casting spells to try to separate a married couple.

Last year, a Lebanese man facing the death penalty on charges of sorcery, relating to a fortune-telling television programme he presented, was freed after the Saudi Supreme Court decreed that his actions had not harmed anyone.

Amnesty says that Saudi Arabia does not actually define sorcery as a capital offence. However, some of its conservative clerics have urged the strongest possible punishments against fortune-tellers and faith healers as a threat to Islam.

4. BBC

'Sorcerer' faces imminent death in Saudi Arabia | |||

The lawyer for a Lebanese man sentenced to death in Saudi Arabia for witchcraft has appealed for international help to save him. Ali Sabat was the host of a popular Lebanese TV show in which he predicted the future and gave advice. He was arrested by religious police on sorcery charges while on a pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia in 2008. His lawyer, May el-Khansa, says she has been told Mr Sabat is due to be executed this week. Ms Khansa has contacted the Lebanese president and prime minister to appeal on his behalf. There has been no official confirmation from Saudi Arabia, but executions there are often carried out with little warning. Mr Sabat did make a confession, but Ms Khansa says he only did so because he had been told he could go back to Lebanon if he did. Human rights groups have accused the Saudis of "sanctioning a literal witch hunt by the religious police". An Egyptian working as a pharmacist in Saudi Arabia was executed in 2007 after having been found guilty of using sorcery to try to separate a married couple. There is no legal definition of witchcraft in Saudi Arabia, but horoscopes and fortune telling are condemned as un-Islamic. Nevertheless, there is still a big thirst for such services in the country where widespread superstition survives under the surface of strict religious orthodoxy. 5. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Saudi Arabia: Witchcraft and Sorcery Cases on the RiseCancel Death Sentences for “Witchcraft” (Kuwait City) - The cassation court in Mecca should overturn the death sentence imposed on Ali Sabat by a lower court in Medina on November 9 for practicing witchcraft, Human Rights Watch said today. Human Rights Watch called on the Saudi government to cease its increasing use of charges of "witchcraft" which remains vaguely defined and arbitrarily used. Ali Sabat's death sentence apparently resulted from advice and predictions he gave on Lebanese television. According to Saudi media, in addition to Sabat, Saudi religious police have arrested at least two others for witchcraft in the past month alone. "Saudi courts are sanctioning a literal witch hunt by the religious police," said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. "The crime of ‘witchcraft' is being used against all sorts of behavior, with the cruel threat of state-sanctioned executions." Religious police arrested Ali Sabat in his hotel room in Medina on May 7, 2008, where he was on pilgrimage before returning to his native Lebanon. Before his arrest, Sabat frequently gave advice on general life questions and predictions about the future on the Lebanese satellite television station Sheherazade, according to the Lebanese newspaper Al-Akhbar and the French newspaper Le Monde. These appearances are said to be the only evidence against Sabat. Saudi newspaper Al-Madina reported on November 15 that a lower court in Jeddah started the trial of a Saudi man arrested by the religious police and said to have smuggled a book of witchcraft into the kingdom. On October 19, Saudi newspaper Okaz reported that the religious police in Ta'if had arrested for "sorcery" and "charlatanry" an Asian man who was accused of using supernatural powers to solve marital disputes and induce falling in love. In March 2008, Human Rights Watch asked a high-ranking official in the Ministry of Justice to clarify the definition of the crime of witchcraft in Saudi Arabia and the evidence necessary for a court to prove such a crime. The official confirmed that no legal definition exists and could not clarify what evidence has probative value in witchcraft trials. Saudi Arabia has no penal code and in almost all cases gives judges the discretion to define acts they deem criminal and to set attendant punishments. In February 2008, Human Rights Watch protested the 2006 "discretionary" conviction and sentencing to death for witchcraft of Fawza Falih, a Saudi citizen. Minister of Justice Abdullah Al al-Shaikh responded that Human Rights Watch had a preconceived Western notion of shari'a, but did not answer the organization's questions about Falih's arbitrary arrest, coerced confession, unfair trial, and wrongful conviction. She remains on death row in Quraiyat prison, close to the border with Jordan, and is reportedly in bad health. November 10, Okaz reported that the Medina court had also issued the verdict for Sabat on a "discretionary" basis. Both Sabat and the Saudi man accused of smuggling books of witchcraft reportedly confessed to their "crimes." Sabat had no lawyer at trial and only confessed because interrogators told him he could go home to Lebanon if he did, according to May al-Khansa, his lawyer in Lebanon. In another case, a Jeddah criminal court on October 8, 2006 convicted Eritrean national Muhammad Burhan for "charlatanry," based on a leather-bound personal phone booklet belonging to Burhan with writings in the Tigrinya alphabet used in Eritrea. Prosecutors classified the booklet as a "talisman" and the court accepted that as evidence, sentencing him to 20 months in prison and 300 lashes. No further evidence for the charge was introduced at trial. Burhan has since been deported, after serving more than double the time in prison to which the court had sentenced him. On November 2, 2007, Saudi Arabia executed Mustafa Ibrahim for sorcery in Riyadh. Ibrahim, an Egyptian working as a pharmacist in the northern town of `Ar'ar, was found guilty of having tried "through sorcery" to separate a married couple, according to a Ministry of Interior statement. "Saudi judges have harshly punished confessed "witches" for what at worst appears to be fraud, but may well be harmless acts," Whitson said. "Saudi judges should not have the power to end lives of persons at all, let alone those who have not physically harmed others." In 2007, Saudi Arabia passed two laws restructuring judicial institutions, and in 2009 began implementing what it said was a comprehensive judicial reform under Minister of Justice Muhammad al-‘Isa, who was appointed in February 2009. However, Saudi Arabia has still not codified its criminal laws, and efforts to update the criminal procedure law, which lacks guarantees against forced confessions such as the right not to incriminate oneself, have not yet come to fruition. Human Rights Watch opposes the use of the death penalty in all circumstances, due to its inherently cruel nature. International standards, for example as expressed in resolution 1984/50 of the UN Economic and Social Council, require all states that retain the death penalty to limit its imposition to the "most serious" crimes. Saudi judges should overturn witchcraft convictions and free those arrested or convicted for witchcraft-related crimes, Human Rights Watch said. King Abdullah should urgently order the codification of Saudi criminal laws and ensure it comports with international human rights standards. | |||

Comments

Post a Comment